Curriculum X and a Radical Rethink of K-12 Education

Our current, siloed curriculum is no longer fit for purpose. What we need is an outcome-thinking approach to redesign. Here's one idea.

In 2017, during a keynote to over two thousand neurosurgeons, Richard Susskind, President of the Society of Computers and Law, suggested that patients don’t really want neurosurgeons. Fearing his audience’s wrath, he quickly followed it with this stinger: what they really want is good health.

Schooling is no different: what employers (and citizens) really want are young people entering the workforce who can solve novel problems, use AI responsibly, and create value in networked markets—not graduates who can pass traditional subject exams. This is even more the case now that AI can pass the majority of these exams on autopilot.

Susskind’s believes (as do I) that we need to move from process-thinking to outcome-thinking:

“Outcome-thinking can be invoked when considering the future of all professions. Take the world of architects. People don’t generally want these experts either. What they really want, as Vitruvius recognised in the first century BC, are buildings that are durable, useful, and beautiful. Nor do taxpayers want tax accountants. They want their relevant financial information sent to the authorities in compliant form… In a similar vein, I spoke not long ago to a group of generals of the British army. My theme then was that ‘citizens don’t want soldiers; they want security’. The same point holds in quite different fields. Patients don’t want psychotherapists. Roughly speaking, they want peace of mind. Litigants don’t want courts. They want their disputes resolved fairly and with finality.”

Extend this to education. Parents don’t want their children to get straight As. What they really want is for them to be financially independent and happy once they leave home to fend for themselves. Straight As are no guarantee of either.

Susskind’s keynote has become a central premise of his most recent book: How to Think About AI: A Guide for the Perplexed. It’s one of the most thought-provoking reads on the current state of AI, both in education and across society. I highly recommend it.

Examining subjects in the light of outcome-thinking

If we dig further, we can see how clearly this extends down into the component parts of our education system. The most obvious of these is the siloed, subject-based organisation of the curriculum. Students do an hour of English, followed by an hour of maths, then break, then more one-hour subjects. Rinse and repeat. Yet, if we shine the light of outcome-thinking onto this structure, we can see how utterly disconnected it is to the world today. If the outcome is future-ready young people, the current process makes little sense.

You can probably argue that the compartmentalised nature of the curriculum has never been optimal—but it’s the best we could manage in the last two hundred years based on the limited amount of human and financial resource available to us. We could never find enough expert English and maths teachers for 1:1 mentorship, nor could we afford it. Mass delivery has been the only viable method to date.

However, the world today does not need students mass taught to answer questions on worksheets, or even write well-crafted essays on the reasons for the First World War (however much it pains me to admit). What it needs are systems thinkers, personal branding experts, and eco-savvy critics of the deeply mediated word they now inhabit. Answering questions 1-10 from page 34 of the workbook must be relegated to history if we are to give students permission to flourish in a world that holds both massive promise, and huge risk.

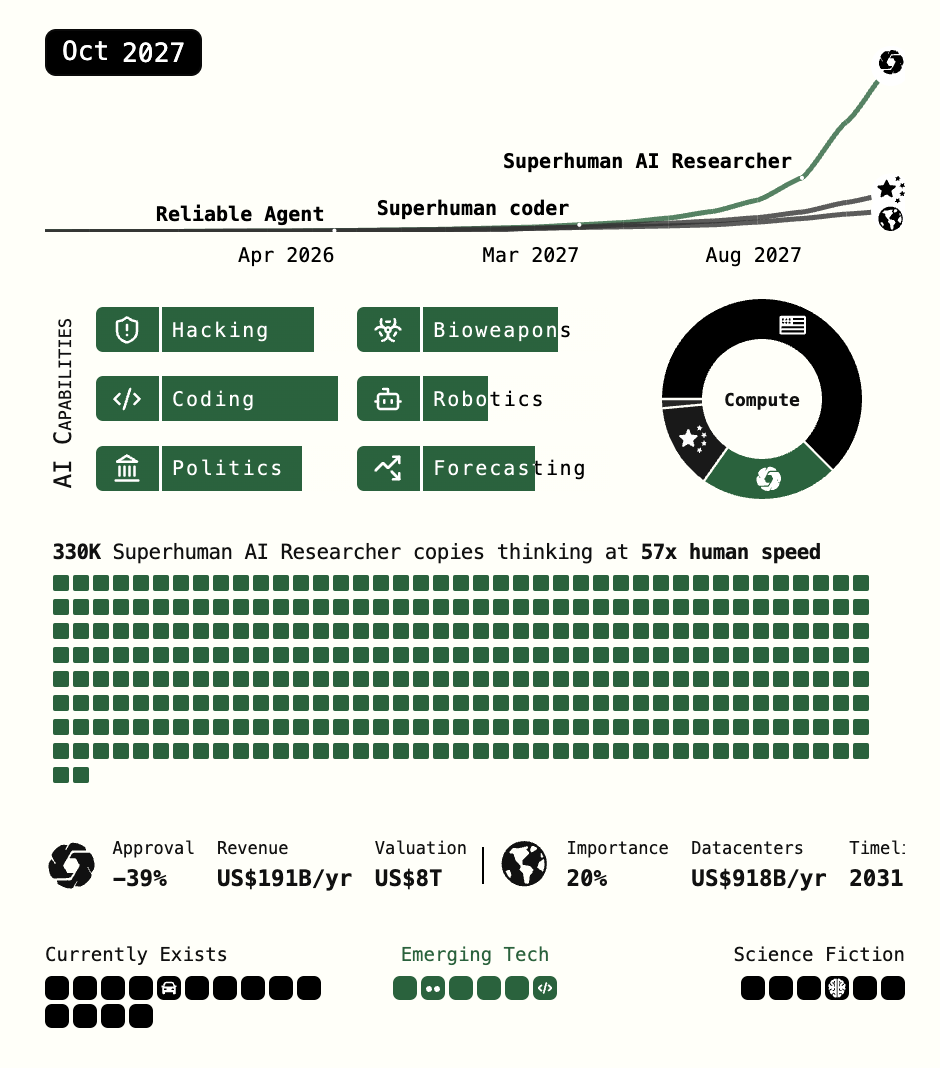

As the AI Futures Project warns, by mid‑2025 we’ll already be using autonomous ‘agents’ that can manage our schedules, code on our behalf, and even brief CEOs on geopolitics. If we don’t equip learners now with the skills to audit and collaborate with such agents, our graduates will be outpaced before they leave school.

Below I make some suggestions. That’s all they are. I don’t have all the answers, but I know some of the questions we should be asking. And one of the most pressing questions is this: what is the role of the curriculum in a world that needs an entirely different skill-set, and where AI tools can do an increasing amount of the work we currently set? Let’s explore.

Curriculum X

I propose an entirely new approach to the delivery of a relevant education, one that is grounded in the outcomes the planet actually needs. ‘Traditional’ subjects are replaced by a domains that face the future, rather than look back to a time long gone. However, this is not a vague mash-up, as we sometimes see in poorly implemented project-based learning. What this is instead is a complete rethinking of what needs to be taught, based on the notion of outcome-thinking.

I refer to it as ‘Curriculum X’ both because it takes into account the cross-domain nature of this new curriculum, and it’s kind of cool—don’t discount this as gimmicky, as giving this a longwinded and academic-sounding name will likely put both teachers and students off.

The below is a team-effort. I cannot take all the credit. This involved working hand-in-hand with ChatGPT-o3, ideating, iterating, challenging and pushing things as far as we could go. o3 tends towards over-complexity, which can be off-putting. I needed to continually ask it to simplify some of the more complex ideas. I think we got there in the end, and although this is only a starting point, it gives plenty of food for thought.

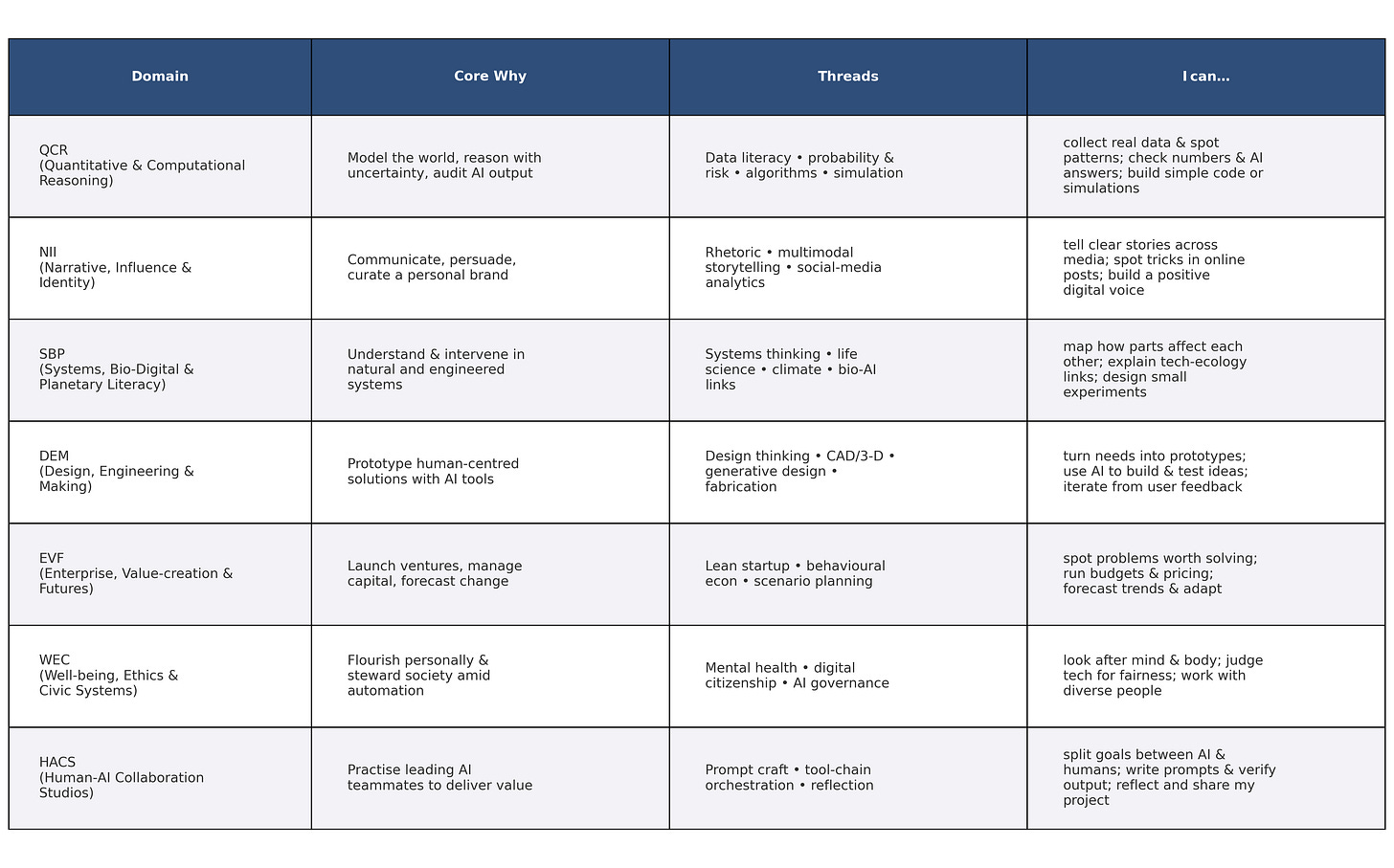

The core curriculum consists of seven domains, each with their own ‘why’, threads, and outcomes. Whilst I suggest direct replacements, it’s not quite so simple, as there are clear overlaps between domains:

Quantitive & Computational Reasoning replaces maths and computing;

Narrative, Influence & Identity replaces English, media, languages, performing arts, and some of the humanities;

Systems, Bio-Digital & Planetary Literacy replaces science and some aspects of geography and sociology;

Design, Engineering & Making replaces art and design technology;

Enterprise, Value-Creation & Futures replaces (to some extent) business and economics, although it goes much deeper and encompasses some elements of art and design;

Wellbeing, Ethics & Civic Systems replaces PSHE, but brings AI literacy and governance inside;

Human-AI Collaboration Studios is truly cross-domain, focusing on the explicit exploration of the intersection between human and AI, considering where human and AI fit in the value chain.

What you sense is how grounded and real-world the domains are: you can understand their usefulness as we enter the second quarter of the 21st century. They move away from the (at times) vague ‘five Cs’ of 21st Century skills into a clear outcomes-focused approach. QCR is all about how we reason with the world and use AI to support that. NII becomes how to navigate an increasingly media-saturated world, and how to craft a personal brand. There must still be a place for literature, but this becomes a study of how writers have explored identity at different times in history (and how history, philosophy, religion and science have shaped that). SBP interweaves the hard and social sciences, coming in at the cross-section of systems. It’s about how we generate a new breed of systems thinkers.

Why keep subjects at all?

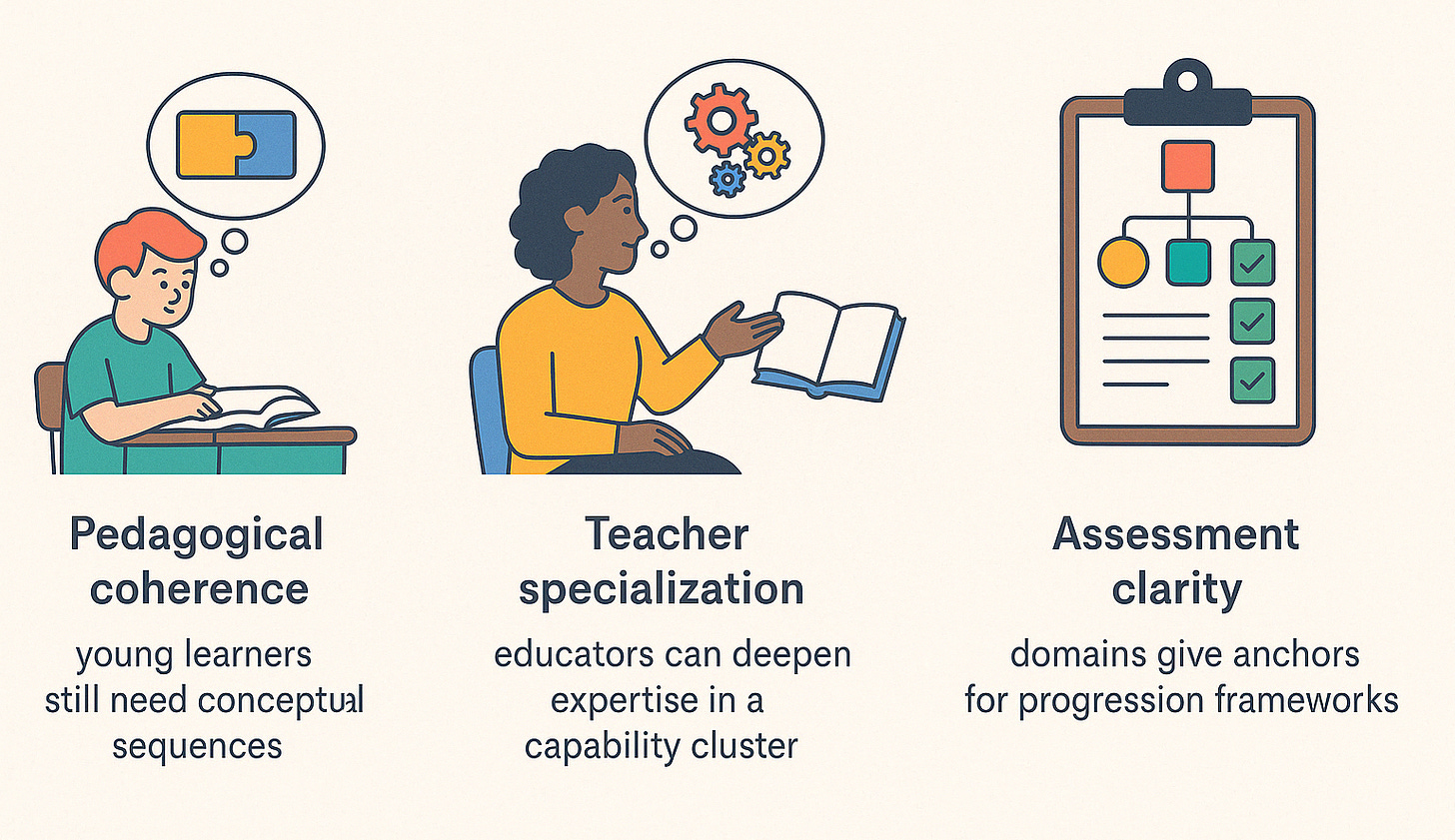

There is argument that we should remove subjects entirely, and focus instead on multidisciplinary project-based learning. The challenge with this is threefold:

Pedagogical coherence—young learners still need conceptual sequences; sprawling PBL alone can leave gaps.

Teacher specialisation—educators can deepen expertise in a capability cluster.

Assessment clarity—domains give anchors for progression frameworks.

But the borders become porous, particularly if we combine the above with two‑day “Studios” each week where teams pull expertise from all domains to tackle community problems with their human and cybernetic classmates.

What this means

Curriculum X combines relevant specialisms with interdisciplinary project work. It enables specialist teachers to remain within their field of expertise whilst reframing their specialisms inside contemporary discourse. It enables students to feel the comfort of subjects that are broadly familiar but rooted in the here-and-now. Above all, it makes education useful and interesting.

There is much work to be done if we are to shift our thinking around curricular redesign. Many challenges await: teacher capacity and mindset, timetabling, accountability and university pathways to name a few. But it feels like these are conversations we must have now, if we are to remain relevant.

And I mean this with utmost earnestness. The now-tired mantra that “AI will never replace teachers” is simply not true. Across many aspects of education, AI can already do just that. What we need are new structures that optimise the relationships within our schools: adult to student, student to student, and both with AI. Perhaps Curriculum X is one step in that direction.

Thanks Darren, the momentum of this conversation has been building for a long time. I can across my Tony Wagner book yesterday Creating Innovators and realised this was published 10 years ago. The Susskind’s book “future of the professions” was 2017.

It is good there is momentum, people like yourself sharing their ideas and Educators and Headteachers using the ideas to make a real difference to our students education.

My question how do we scale without breaking an education system already tottering under the pressure to implement statutory requirements?

Reminds me a lot of London Interdisciplinary School (LIS) and threshold concepts as well as Minerva. The key question here - how do we 1) motivate young people and 2) prepare them are the central questions of our book and I love this provocation. Thanks Darren.